https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/climate-change-inequality-global-warming-temperature-rising-sudan-uk-india-canada-norway-a8881526.html

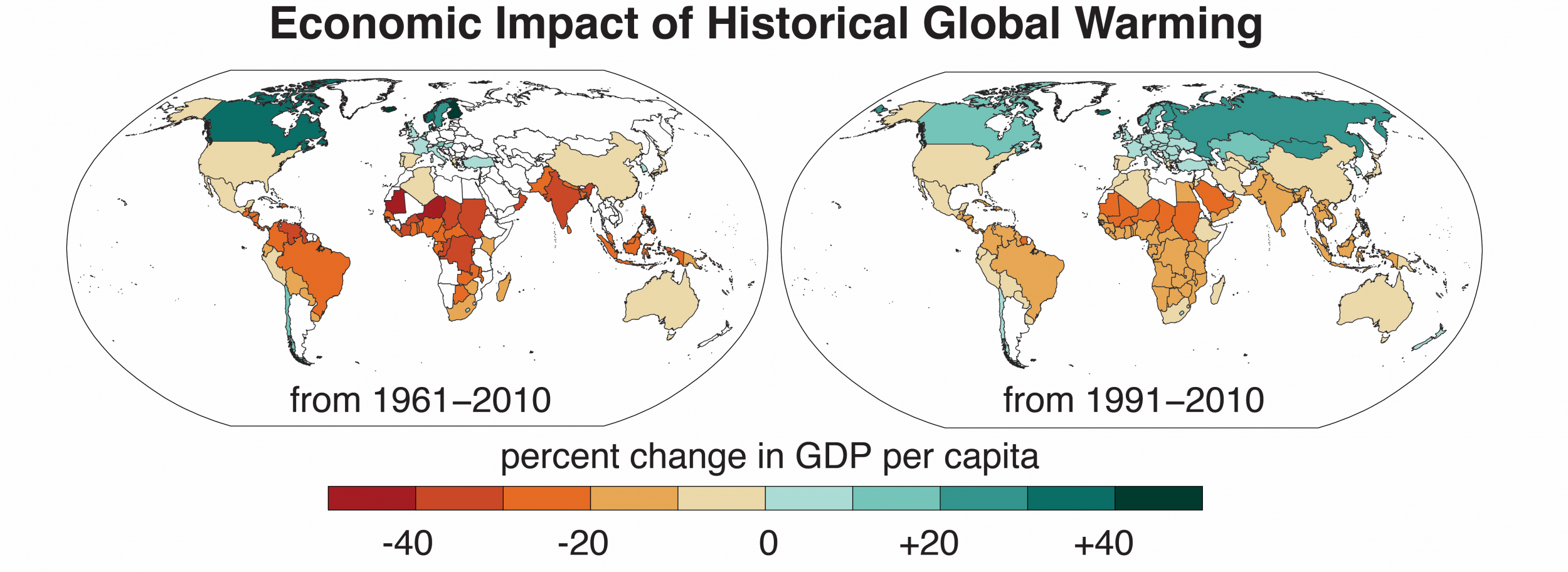

Over the past 50 years climate change has served to make the poorest countries in the world “considerably poorer”, while enriching some of the wealthiest and most polluting, a study has found.

Increasing global temperatures are set to worsen natural disasters, droughts and famines that could displace millions in future, but US researchers have shown they have already caused decades of worsening inequality.

Research, led by Stanford University, shows between 1961 and 2010 wealth per person in the world’s poorest countries was between 17 to 30 per cent lower that would have been expected without global warming.

While equatorial nations in Africa, Asia and South America have been hardest hit by hotter temperatures, those at more northerly latitudes – like Canada and Norway – have seen their economies grow by a third.

The UK’s economy today is 10 per cent larger than it would have been without man made warming, while Sudan’s – the hardest hit nation – is 36 per cent smaller.

Show all 46

“The historical data clearly show that crops are more productive, people are healthier and we are more productive at work when temperatures are neither too hot nor too cold,” Dr Marshall Burke, an earth system scientist and author of the research said.

“This means that in cold countries, a little bit of warming can help. The opposite is true in places that are already hot.”

This environmental inequality is made worse by the fact that wealthier nations, who have seen their GDP improve by 10 per cent on average thanks to warming, are also the biggest emitters of greenhouse gasses driving climate change.

The world’s lowest emitters over the past 50 years have seen their GDP fall by around 25 per cent.

“This is on par with the decline in economic output seen in the US during the Great Depression,” Dr Burke said. “It’s a huge loss compared to where these countries would have been otherwise.”

Like saving into a high interest account, these small losses in crop yields or human productivity in the 1960s amount to big losses over decades, particularly with temperatures worsening.

India’s economy, for example, is 31 per cent smaller than it would have been without warming.

The research published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences used estimates from 20 different climate models. These models help predict how temperatures might change with different levels of greenhouse emissions around the world but also show how they had changed, and can be compared alongside economic predictions.

Dr Burke and colleagues recognise that there are high levels of uncertainty in climate and economic modelling, particularly among nations like the US and China who were in the temperate range to begin with.

While these large economies may not have suffered yet, and may have benefited, Dr Burke said this won’t always remain true.

“A large amount of warming in the future will push them further and further from the temperature optimum,” he said.

沒有留言:

張貼留言