http://e-info.org.tw/node/117182

這款洗衣球不洗衣 專門攔截「微纖維」護海洋

文字大小

2410 3 Share1

本報2016年7月25日綜合外電報導,鄒敏惠編譯;詹嘉紋審校

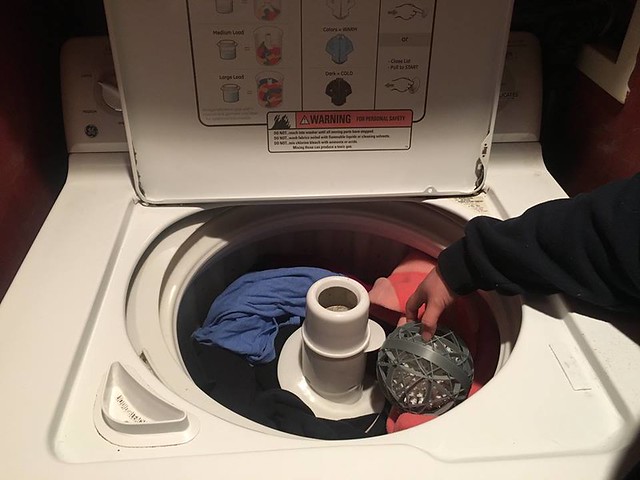

市面上第一種專門過濾微纖維的「洗衣球」,有望在明年春季上市!服飾上大量脫落的微小纖維,順著洗衣廢水進入河川、海洋,已成為各個水域最大宗的塑膠垃圾之一,污水處理廠也束手無策。國外有環團和科學家共同研發,民眾只要在洗衣時放入一顆特製的洗衣球,與其他衣物一起清洗,就能攔截這些比頭髮還要細小的人造纖維。

這種洗衣球是一個塑膠中空圓球,直徑約八英寸,中間機芯的形狀設計就像海葵,其功能也與海葵在水流通過時攫取細小的蜉蝣生物相似。「我們希望藉由水流的力量,抓取微小的東西。」海洋保育團體羅撒莉亞計畫(Rozalia Project)創始人之一的米勒(Rachael Miller)說道。

「它會在你家的洗衣機內遊走,攫取人造纖維,還會偶有加碼演出,一併把毛髮聚集起來。」米勒說,「它會做兩份工作。」

|

| 洗衣球實測,發現不只攫取出微纖維,還有毛髮。圖片來源:Rozalia Project。 |

研發團隊表示,目前已完成幾款常見洗衣機的測試,預計在明年春季上市,零售價格約為20至25美金(約新台幣640至800元)。

每個家庭洗衣的頻率不同,機芯的壽命也不一樣。米勒表示,以一家四口再養一隻狗的家庭來說,一顆洗衣球可使用六到八週,之後研發團隊將把新的機芯寄到府上,供民眾將使用過的機芯以原包裝寄回,由計畫團隊妥善回收。

一份2011年的研究顯示,在全世界海岸的人為垃圾中,微纖維竟佔了85%。最新研究顯示,一件普通的刷毛夾克丟進洗衣機,洗一次就會釋出約25萬條微纖維。微小的纖維很容易被魚類和其他野生動物攝食,且可能有生物累積效應,含量隨著食物鏈越來越高。

「我們都必須穿衣服、洗衣服,這是所有人都要面對的問題。」米勒表示。

至於在洗衣球上市前,你可以怎麼做呢?「我們建議你不要太常洗衣服,除非真正需要的時候。」米勒說,「這真的是目前最好的辦法。」

洗衣球實測,攫取出的微纖維放大照片。圖片來源:Rozalia Project。

【相關文章】

【參考資料】

- Newport This Week (2016年7月7日),A Major Endeavor to Clean Oceans of Microfibers

- Boston Magazine(2016年5月19日),The Rozalia Project Wants You to Stop Polluting the Ocean

A Major Endeavor to Clean Oceans of Microfibers

Vessel Collects Invisible Threats in New England Waters

That could be the conclusion of the scientists aboard the American Promise, a 60-foot research vessel that has sailed for four weeks along the waters fromKittery, Maine, to Cape Cod Canal, through New York Harbor to Albany, N.Y., down the Hudson River, outLong Island Sound from the Battery to the Race, toNewport and back.

Part of the Rozalia Project, a crew of nine has collected 139 sample bottles of water [plus an additional 50 for partners], which will be studied in a lab when the ship returns to Kittery later this week.

The vessel docked for just one night at Fort Adams, and Rachael Miller, captain and co-founder of the project, explained the project’s purpose – to protect and clean the ocean from the surface to the sea floor by identifying microscopic marine debris, usually smaller than a human red blood cell.

“We use technology to develop solutions to clean up marine debris. This expedition is dedicated to synthetic microfiber solutions. Our clothing is breaking up and washing out of washing machines into public waters. All of the synthetics – dacron, plastics, rayon, polyesters – are breaking down,” said Miller. “A thread is really many, many threads. For lack of a better term, we’re eating our bicycle pants, our ski pants, our workout clothing. Science did not even know about this breakdown five years ago.”

Shellfish and fish eat the fibers first, and Miller points to independent scientific research confirming this. There are also suspicions that toxins such as DDT and PCBs, among others, stick to the fibers, causing havoc with marine reproductive cycles. We, of course, then consume the seafood.

“I don’t eat fish, but have relatives who do and I don’t want them eating plastic,” said Miller.

The captain took visitors down below to the center of the vessel, where she held a magnifying device to a shirt, then shorts, and even to a sneaker, revealing thousands upon thousands of microfibers ranging from 70 microns to just three microns in just one tiny section. “A red blood cell is seven to eight microns. These are really small,” she said.

But the Rozalia Project – which Miller named after her great-grandmother who brought her grandmother to America aboard a small vessel for a better life – is also working on the solution to the problem: a microfiber catcher.

An open hollow plastic ball about eight inches in diameter, with what looks like a sea anemone at its core, the catcher goes inside washing machines during the standard washing cycle.

“We want the water to flow and we want to catch the little things,” said Miller. Tested in the most popular types of washing machines (according to Rozalia’s correspondence with large vendors such as Lowe’s and Home Depot), the team hopes the device – which they plan to retail at about $20 with replaceable core collectors – will be available for use in washers by next spring.

“We hope to market it with subscriptions, partnering with businesses in filling and replacing the element inside,” said Miller. One tentative plan would be to have consumers sign up for a subscription so that a new inner catcher is mailed around the time it needs to be replaced. The consumer would then send the used catcher back in the same box for recycling.

Miller said a family of four with a dog would likely have to replace the device every eight weeks, but more development is in the offing.

Tuthill, whose photography and videography have detailed the summer excursion in brilliant detail, got involved after biking through Fort Wetherill in Jamestown and seeing a shocking amount of trash along, and in, the water.

“I’m a senior in college, a native islander, and I started documenting the pollution,” she said. “My dad let me know about this internship. I thought it was the coolest thing ever, I applied, and Rachael Miller called me and said, ‘Come aboard.’ I feel as if I’ve learned so much. It has been a privilege to be here, using my photography skills to do something near and dear to my heart.”

In fact, the Rozalia Project’s roots date locally to 2010, when it partnered first with Sail Newportand Providence Community Boating. The ship left Newport Wednesday for a stop at Patagonia Clothing in Boston, giving a free interactive presentation of their cause and how the public can help.

“The challenges are immense. We made this problem, but we believe we can fix it. With the microfiber catcher, we think we can make the biggest impact we have ever made,” Miller said.www.rozaliaproject.org.

The Rozalia Project Wants You to Stop Polluting the Ocean

Each time you wash your clothes, synthetic microfibers are released into our waterways.

THE ROZALIA PROJECT’S MICROFIBER CATCHER/PHOTO PROVIDED

Whether you know it or not, you’re polluting the ocean.

Each time you wash clothes made with synthetic materials—think polyester, rayon, nylon, and the like—as many as 1,900 tiny microfibers break off, flow through your washing machine drain, and continue on to waterways. Once in the water, they’re ingested by all forms of marine life, threatening both their health and yours. Consider this: In a 2015 study, 67 percent of species purchased from a California fish market were found to contain microfibers, meaning there’s a very real chance that plastic is ending up on your plate.

There’s not conclusive data about what, exactly, microfibers do to human health, but Rachael Miller, co-founder of the New England-based ocean conservation group Rozalia Project, says it’s safe to assume they’re not a desirable part of your seafood spread.

“I don’t want to eat my fleece, and I don’t want to eat your fleece, and my guess is you don’t want to eat the guy down the hall’s fleece, either,” she says. “Whatever the consequences are to humans, none of us are willingly eating synthetic anything.”

To prevent you from eating your fleece, and the fleeces of thousands of strangers, Miller and Rozalia Project are working to curtail microfiber pollution, a problem that has only come to light as water testing methods have grown more sophisticated in recent years. But, lucky for athleisure addicts, Miller says outlawing synthetics isn’t what Rozalia Project is about. “A little synthetic in your yoga pants helps,” she laughs. “Let’s not pretend it doesn’t!”

Instead, the group is developing what Miller says is the market’s first microfiber catcher, a small sphere that you’d throw in the washing machine just as you would a dryer ball. The design, Miller says, is modeled after creatures like sea anemones, which allow water to pass through them while catching tiny plankton.

“It will cruise around your washing machine and collect synthetic microfibers, and as a kind of awesome added bonus, it seems to be collecting hair pretty effectively as well,” Miller says. “It’s doing double work.”

The product will ideally go on sale next spring, and Miller guesses it will cost between $20 and $25. Roughly every six to eight weeks, users will send their filled catcher—which Miller says will resemble a “sort of colorful hairball”—back to Rozalia Project, which will safely dispose of the microfibers and send a new catcher back.

“This is a problem that we’re all part of, everyone who wears clothes and then washes them,” Miller says. “There’s no reason to feel bad about that. We didn’t know this was happening. But now we know, so we feel that we’re providing an opportunity to be part of the solution—and an easy way.”

As for what you can do until the product comes to market, Miller says it’s a pretty simple solution. “We recommend washing your clothes only when they really need it,” she says. “That’s really the best we can do right now.”

沒有留言:

張貼留言