https://news.sky.com/story/climate-crisis-how-antarctica-could-unleash-hell-in-just-a-few-short-decades-11889776?fbclid=IwAR0tkxWlTnk3K6k07i7a8kQXFb36fqA6jqXwvMrYcFteTXRDKCGVN1NFSUg

Climate crisis: Scientists brave the cold to study the hell that Antarctica could unleash

Sky's Thomas Moore is on a mission to the bottom of the planet to find out why what happens there affects us all.

Monday 30 December 2019 11:27, UK

There's a place on our planet where it's so cold that humans could only take a few breaths before their lungs would haemorrhage.

It's on the high dome of the East Antarctic ice sheet, where, during the long, dark polar night, satellites have recorded the temperature plunging as low as -98C (-144F).

Antarctica is a hostile continent. The katabatic winds that whip down from the 4,000m (13,123ft) heights to the coast regularly reach hurricane force. The record is 199mph.

And then there's the ice, so thick it buries an entire mountain range. At one point - the Astrolabe basin - it's 4,776m (15,669ft) from top to bottom. That's almost three miles.

By any measure, Antarctica is not a natural place for humans. So remote it was only discovered 200 years ago, so wild that it was barely a century ago that Roald Amundsen pipped Robert Scott in the race to the Pole.

And yet scientists are now racing south, braving the conditions to study, with growing horror, the hell that Antarctica could unleash as the world warms.

It has lost three trillion tonnes of ice over the last 25 years. Half of that has been in the last five years.

All that fresh water - and Antarctica has about 70% of the global total - is raising sea levels.

At the start of the last century, the water was creeping upwards at just over 1mm a year. Now it's 3mm - and accelerating.

It doesn't sound much, unless you live on a low lying island, like the Maldives or Kiribati, already losing land to the sea.

:: A New Climate is a series of special podcasts from the Sky News Daily. Listen on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Spreaker

But scientists can't rule out a 2m (6.5ft) rise by the end of the century. Spring tides and storm surges could drive up the level even more.

New York, Miami, Calcutta, Lagos and other great cities could be flooded. One billion people could be forced to move.

That could already be baked in to our future, regardless of efforts to reduce global emissions of greenhouse gases.

And it won't stop there. The sea will continue to rise, and at an even faster rate, in the 22nd century - the start of which is now within the lifetime of children being born today.

To understand the threat of Antarctica's melting ice, you need to understand the topography.

Scrape away the ice sheet and large parts of Antarctica actually lie up to 2,500m (8,200ft) below sea level. Only a rim of higher land along the coast stops the sea from flooding in.

But as sea levels rise, a torrent of water could slip beneath the ice and begin to melt it from beneath.

The 2.2 million cubic kilometres of the Western Antarctic Ice Sheet are particularly vulnerable.

If it melts, it could add another 3m (10ft) to the global sea level - on top of the 2m that scientists already believe is possible.

On the eastern side of Antarctica the Wilkes ice sheet is also at risk - and could add yet another 4m (13ft) to sea level.

So that's 9m (29.5ft) in all: enough to redraw coastlines around the world.

It's happened in the past.

Three million years ago carbon dioxide levels were much the same as they are today.

Temperatures were a degree or two warmer. But sea levels were 20m to 25m higher.

That's a lot of numbers, but they're important because it could be the world we are returning to.

Scientists writing in the journal Nature recently warned we were perilously close to the tipping point. Temperatures are expected to climb past 1.5C by 2030, committing our descendants to a watery future.

The scientists didn't mince their words. They said the melting ice in Greenland and particularly Antarctica was "an existential threat to civilisation".

Whether that happens in the timescale of centuries or millennia may well depend on our success in rapidly reducing greenhouse gas emissions over the next few decades.

By then, the wildlife that we associate with Antarctica is likely to be long gone.

Two species of penguin are utterly dependent on the frozen habitat.

The Emperor, which can weigh 40kg, making them the biggest penguins of all, could virtually disappear by 2100.

The males spend the Antarctic winter on the apron of sea ice surrounding the continent, balancing a single egg on their feet, huddled together against the elements.

But already entire colonies are suffering successive years of breeding failure, with the ice breaking up before the young are raised.

As the decades pass, they'll run out of suitable ice altogether.

It's a similar story with the Adelie penguin.

Already numbers on the Antarctic Peninsula, the finger of land that stretches up towards South America, have slumped.

As the climate warms, their nests are being flooded and the eggs drowned. Colonies that used to number in the thousands have in some cases dwindled down to the hundreds.

Nesting sites are now being taken over by Gentoo penguins following the warmer weather south. They're more adaptable, able to have a second clutch of eggs if the first fails. And the species is doing well, one of the winners in the climate change story.

British Antarctic Survey has been studying the frozen continent since the 1960s.

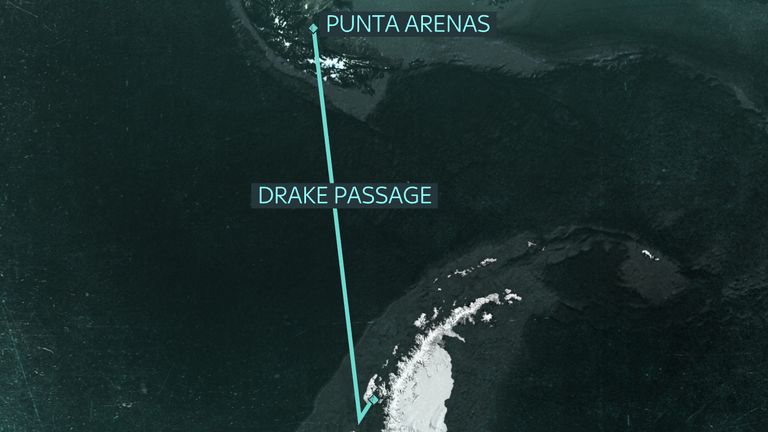

Sky News will join scientists on the Royal Research Ship (RSS) James Clark Ross for the 1,300-mile voyage south from Punta Arenas at the tip of Chile, across the notoriously rough Drake Passage to Rothera, BAS's main science base on the Antarctic Peninsula.

From there we will head north again to study three fjords where glaciers that used to flow into the sea are retreating rapidly, exposing the water to light for the first time in thousands of years.

It'll be the third consecutive year that the scientists have been to the fjords to track changes to the water and the life within.

It's a critical piece in the Antarctic puzzle. How quickly is the ecosystem changing? Over a wider scale, will the blooming marine life absorb more carbon dioxide and lock it away at the bottom of the sea?

Understanding the rapid changes in Antarctica has never been more vital. The faster we reduce emissions the more of the ice we save and the slower the rise in sea level.

Britain may be 10,000 miles away, but what happens at the bottom of the planet matters to us all.

Thomas Moore will be writing a daily blog about what he sees and finds in Antarctica for Sky News and filing regular reports on what he discovers. Follow his progress here.

沒有留言:

張貼留言