https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/mar/11/polar-ice-caps-melting-six-times-faster-than-in-1990s

Polar ice caps melting six times faster than in 1990s

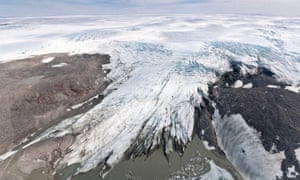

Losses of ice from Greenland and Antarctica are tracking the worst-case climate scenario, scientists warn

The polar ice caps are melting six times faster than in the 1990s, according to the most complete analysis to date.

The ice loss from Greenland and Antarctica is tracking the worst-case climate warming scenario set out by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), scientists say. Without rapid cuts to carbon emissions the analysis indicates there could be a rise in sea levels that would leave 400 million people exposed to coastal flooding each year by the end of the century.

Rising sea levels are the one of the most damaging long-term impacts of the climate crisis, and the contribution of Greenland and Antarctica is accelerating. The new analysis updates and combines recent studies of the ice masses and predicts that 2019 will prove to have been a record-breaking year when the most recent data is processed.

The previous peak year for Greenland and Antarctic ice melting was 2010, after a natural climate cycle led to a run of very hot summers. But the Arctic heatwave of 2019 means it is nearly certain that more ice was lost last year.

The average annual loss of ice from Greenland and Antarctica in the 2010s was 475bn tonnes – six times greater than the 81bn tonnes a year lost in the 1990s. In total the two ice caps lost 6.4tn tonnes of ice from 1992 to 2017, with melting in Greenland responsible for 60% of that figure.

The IPCC’s most recent mid-range prediction for global sea level rise in 2100 is 53cm. But the new analysis suggests that if current trends continue the oceans will rise by an additional 17cm.

“Every centimetre of sea level rise leads to coastal flooding and coastal erosion, disrupting people’s lives around the planet,” said Prof Andrew Shepherd, of the University of Leeds. He said the extra 17cm would mean the number of exposed to coastal flooding each year rising from 360 million to 400 million. “These are not unlikely events with small impacts,” he said. “They are already under way and will be devastating for coastal communities.”

Erik Ivins, of Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in California, who led the assessment with Shepherd, said the lost ice was a clear sign of global heating. “The satellite measurements provide prima facie, rather irrefutable, evidence,” he said.

Almost all the ice loss from Antarctica and half of that from Greenland arose from warming oceans melting the glaciers that flow from the ice caps. This causes glacial flow to speed up, dumping more icebergs into the ocean. The remainder of Greenland’s ice losses are caused by hotter air temperatures that melt the surface of the ice sheet.

The combined analysis was carried out by a team of 89 scientists from 50 international organisations, who combined the findings of 26 ice surveys. It included data from 11 satellite missions that tracked the ice sheets’ changing volume, speed of flow and mass.

About a third of the total sea level rise now comes from Greenland and Antarctic ice loss. Just under half comes from the thermal expansion of warming ocean water and a fifth from other smaller glaciers. But the latter sources are not accelerating, unlike in Greenland and Antarctica.

Shepherd said the ice caps had been slow to respond to human-caused global heating. Greenland and especially Antarctica were quite stable at the start of the 1990s despite decades of a warming climate.

Shepherd said it took about 30 years for the ice caps to react. Now that they had a further 30 years of melting was inevitable, even if emissions were halted today. Nonetheless, he said, urgent carbon emissions cuts were vital. “We can offset some of that [sea level rise] if we stop heating the planet.”

The IPCC is in the process of producing a new global climate report and its lead author, Prof Guðfinna Aðalgeirsdóttir, of the University of Iceland, said: “The reconciled estimate of Greenland and Antarctic ice loss is timely.”

She said she also saw increased losses from Iceland’s ice caps last year. “Summer 2019 was very warm in this region.”

We've got an announcement…

… on our progress as an organisation. In service of the escalating climate emergency, we have made an important decision – to renounce fossil fuel advertising, becoming the first major global news organisation to institute an outright ban on taking money from companies that extract fossil fuels.

In October we outlined our pledge: that the Guardian will give global heating, wildlife extinction and pollution the urgent attention and prominence they demand. This resonated with so many readers around the world. We promise to update you on the steps we take to hold ourselves accountable at this defining point in our lifetimes. With climate misinformation rife, and never more dangerous than now, the Guardian's accurate, authoritative reporting is vital – and we will not stay quiet.

We chose a different approach: to keep Guardian journalism open for all. We don't have a paywall because we believe everyone deserves access to factual information, regardless of where they live or what they can afford to pay.

Our editorial independence means we are free to investigate and challenge inaction by those in power. We will inform our readers about threats to the environment based on scientific facts, not driven by commercial or political interests. And we have made several important changes to our style guide to ensure the language we use accurately reflects the environmental emergency.

The Guardian believes that the problems we face on the climate crisis are systemic and that fundamental societal change is needed. We will keep reporting on the efforts of individuals and communities around the world who are fearlessly taking a stand for future generations and the preservation of human life on earth. We want their stories to inspire hope.

We hope you will consider supporting us today. We need your support to keep delivering quality journalism that’s open and independent. Every reader contribution, however big or small, is so valuable. Support the Guardian from as little as $1 – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.

沒有留言:

張貼留言